Public discourse, the language we use in our exchanges with each other, in the media and in political debates, shapes and guides our perception of what happens around us. Put differently, the choice of words and metaphors contributes to the way we view the world.

The Team

Del Fante’s background is in linguistics and literature, discourse analysis and cognitive studies. He is Assistant Professor in English language, linguistics and translation at the University of Ferrara. Zorzi is a research fellow at the University of Bergamo, with a PhD in linguistics. Her background is in applied linguistics, discourse analysis and translation studies, and she often draws on methods related to corpus linguistics.

The two first met in 2017, during a summer school in the UK, but crossed paths again at the University of Padova, where they both enrolled in the same PhD programme. Del Fante explains: ‘We already had some research interests in common, both in terms of topic and in terms of methods, and we became friends as well. We decided it would be good to work together whenever possible, and we have been doing so ever since.’ (For examples of previous collaborations, see here).

Del Fante has been interested in migration for some time. He sees migration as an age-old phenomenon, a ‘characteristic of humanity’. Del Fante’s PhD focused on the metaphorical representation of migration in the newspaper discourse in the US and Italy. Zorzi recently started working on the topic as part of her current fellowship project on migration discourses.

‘We share the same perspective on migration, and the belief that the way we speak about migrants and migration in general has significant social impact. We feel that this is a very urgent, topical theme, and that we need to pay attention to it.’ Zorzi explains.

I think we share the same perspective on migration, and that the way we speak about migrants and migration in general has significant social impact. We feel that this is a very urgent, topical theme, and we need to pay attention to it.

–Virginia Zorzi

The Project

In their recent project ‘Who is the Enemy Now?’, Del Fante and Zorzi explore the discourse around migration during 2015/16 and 2020. The project is not funded, meaning Del Fante and Zorzi work on it in their own time out of conviction. They focus their analysis on the discourse in Italy and the UK because both countries have long histories of public debate around migration, and both also receive a comparatively large number of migrants. In addition, both researchers are Italian native speakers, with an academic background in English language, which was the practical reason for the choice of the two case studies.

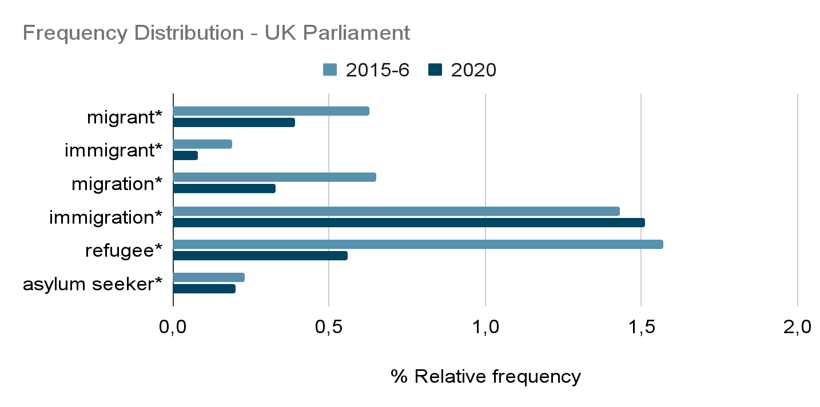

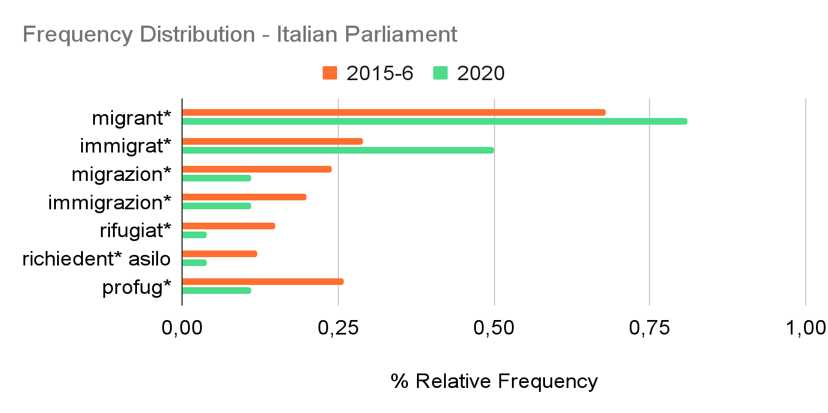

The project uses interdisciplinary methods, predominantly corpus-based analysis of the representation of migration and migrants in British and Italian newspapers and parliamentary debates (as found in the ParlaMint dataset). The diachronic analysis compares the discourse in 2015/16, when the so-called European migration crisis took place, with 2020, when COVID-19 first hit the world, with migrants being disproportionately affected by the pandemic.

The aim was to examine whether there was any difference in the representation of migration and migrants between the languages and time points, by focusing on the occurrences of single words (for example, ‘migrante’/’migrant’, ‘immigrazione’/’immigration’) and common metaphors.

Outcome

Based on their findings, migrants tend to be associated with similar words and concepts in both time periods studied. In the newspaper discourse in 2015/16, the collocational profile of ‘migrant(s)’ and ‘migrante/i’ is rather similar in both countries. Migrants tend to be associated with similar ranges of semantic domains, such as numbers and quantifying expressions (‘hundreds’, ‘thousands’, ‘number (of)’), expressions referring to and describing the migration process from the perspective of the in-group (i.e. ‘arriving’, ‘crossing’, ‘reaching’), the concept of crisis and/or emergency, and a metaphorical representation of migration as a liquid (‘wave’, ‘flow’, ‘influx’).

It is noteworthy that these similarities are present despite the fact that the political and historical backgrounds of the two countries differed during that period: the Italian government was headed by Matteo Renzi and included ministers with various political orientations, mainly from the left-wing Democratic Party, while the UK was governed by David Cameron of the Conservative Party, and had recently voted to leave the EU. That said, specific events in each country (e.g. Brexit or national elections) were not considered in this first analysis.

Moreover, in both time periods, the migrant categories appearing in the UK included ‘workers’, ‘refugees’ and ‘economic migrants’, whilst in Italy the category of ‘worker’ is not used as a way to categorise migrants. This might point to differences in the public perception of migrants in the two national contexts, although further analysis is needed to confirm that.

Migration discourse in the Italy during the pandemic (2020) shows that migration was connected to COVID-19 as a result of the association between ‘migranti’ (migrants) and ‘positivi’ (migrants who tested positive for COVID-19), and the association between ‘migranti’ (migrants) and ‘quarantena’ (migrants who had to quarantine upon arrival). In this sense, the findings suggest that migration was seen as an additional problem of the pandemic.

The analysis also shows some shifts over time. For example, the use of the water metaphor seems to have decreased from 2015/16 to 2020. The use of ‘crisis’ was strongly associated with migrants, especially in the news, but also in parliamentary discourse, in 2015/16, but not in 2020. It is possible that the use of terms such as ‘influx’ and ‘crisis’ could have shifted towards the representation of COVID-19, but more analysis is needed to explore this in more detail.

This [analysis] is a tool for democracy. It could be useful and have an impact, if it is disseminated appropriately.

–Virginia Zorzi

Working with the ParlaMint Dataset

Future Directions

In the future, they hope to go beyond single word queries, and plan to use the NoSketchEngine interface to focus on, for example, specific grammatical forms, adjectives and evaluative language. The NoSketchEngine would also allow them to analyse specific politicians’ language use and compare their statements, which would provide additional context. In Del Fante’s view, ‘right-wing populist parties seem to play a role in the spreading of similar frames of interpretation and representations of migration in recent years.’

In due time, they hope to publish their work after peer review and would like to see it shared with the wider public through outreach activities, for example in higher education institutions or via media channels.

Taking additional languages into account would also be an interesting extension of the project, though no specific plans have been made yet. The big dream, Zorzi explains, would be to ‘create a kind of big, massive task force made up of different countries from the European area, and beyond.’

ParlaMint, which they both plan to use again, would certainly allow for more languages to be studied, and its association with the CLARIN network could get more researchers interested in the topic. In Del Fante’s view, CLARIN is ‘essential for the future of research. Resources on open access are fundamental for the future of our life. Knowledge is the sharing of knowledge. Open access resources are too important now.’

CLARIN is essential for the future of research. Resources on open access are fundamental for the future of our life. Knowledge is the sharing of knowledge. Open access resources are too important now.

–Dario Del Fante