The Project

Parliamentary debates are at the heart of political decision-making; they represent political power. Identifying social patterns and power relations within parliament is crucial, as they have an effect on these debates and, ultimately, on national legislation. This project examines different aspects of power in parliamentary discourse in three European countries, with a particular focus on gender distribution in the debates.

Interdisciplinary Team

The Objective

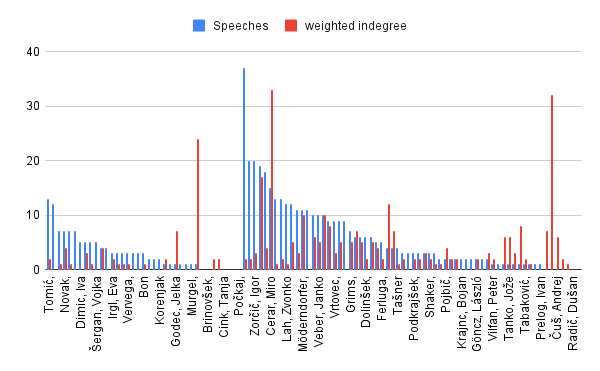

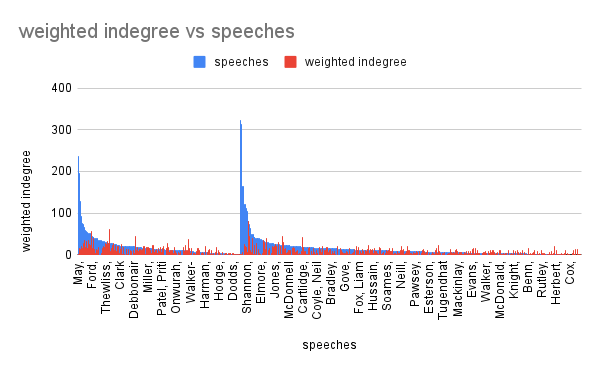

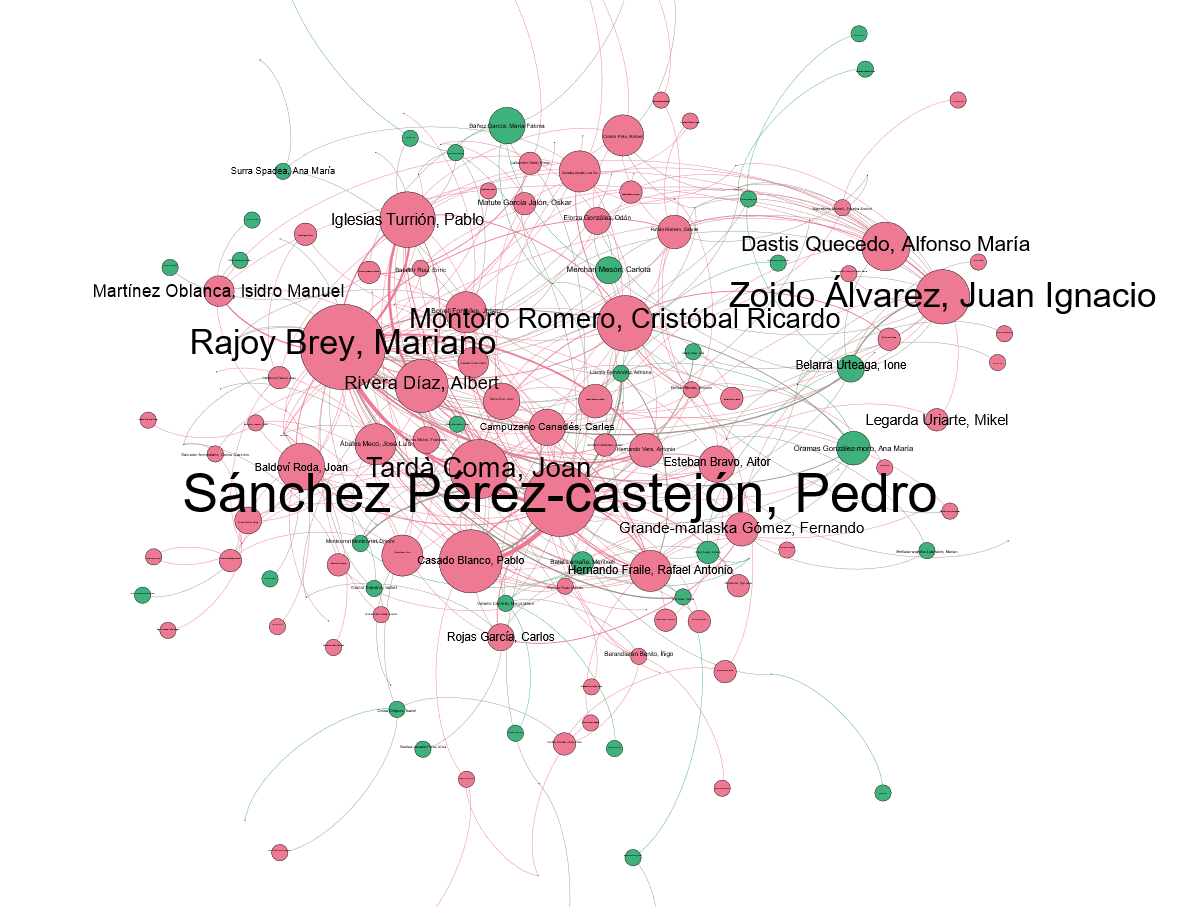

The project’s primary objective was to gain insight into the power distribution of parliamentarians in different national parliaments in Europe, using statistical and social network analysis on transcribed parliamentary debates. Power and relevance were considered to be proportionally related - the more power an MP holds, the higher their relevance inside parliament and vice versa. The team measured argumentative power through the relative amount of speeches per member, which were defined as Active Relevance (AR), and the relative amount of mentions by others, which were defined as Passive Relevance (PR). While high AR shows high active participation in the debates, high PR suggests high importance for the discussions in the parliament.

In addition, the team analysed structural power through the gender distribution of argumentative power within selected topics that are typically seen as ‘hard’, such as energy and finance, or ‘soft’, such as healthcare and education.

Methodology

The researchers selected three parliaments to analyse: Slovenia’s Državni zbor, Spain’s Congreso de los Diputados, and the United Kingdom’s House of Commons, all of which correspond to the lower house. The analyses were based mainly on the ParlaMint dataset, which contains session transcriptions from more than 17 European national parliaments, across multiple parliamentary terms. The corpora are uniformly encoded, contain rich metadata of 11 000 speakers, and are linguistically annotated using the Universal Dependencies standard and with named entities.

In order to measure MPs’ argumentative power in the three parliaments, and observe how this power scheme relates to gender, the team made use of ParlaMint’s metadata to divide the speakers into men and women. MPs’ active participation in debates (AR) was calculated using the subset ‘unique speeches’ in the ParlaMint dataset, that is, the number of speeches given by individual MPs. In order to calculate MPs Passive Relevance, the speeches in the ParlaMint dataset were annotated with named entity (NE) tags using language-specific machine learning models. Using the NE tags, the team then detected speech parts in which one MP mentions another MP. The relative number of times an MP was mentioned in someone else’s speech was taken as the Passive Relevance score.

The structural power within parliament was examined by applying speech selection to five topics: energy, finances, healthcare, education, and immigration. The topic modelling was carried out with a manual procedure using keywords. Keyword sets were identified for each topic using a careful qualitative and iterative process with the help of the NoSketch Engine system, which allows manual browsing through large datasets.

Outcome

The distributions with the most women MPs were the list of top 20 mentions for the UK (7), and the top 20 speeches for Spain (5). The lowest number of women MPs (1) could be found in the distribution of mentions for Slovenia. Generally, the distribution of mentions was to a great extent determined by the government position held by MPs.

There was less evidence for the same impact on gender distributions of specific topics in all three countries. The results imply that the dichotomy between ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ topics may not be universally valid, but varies from parliament to parliament. Healthcare, for instance, one of the topics predefined by the researchers in the team as ‘soft’ (i.e. associated with women), presented distinctly women-dominated AR in all parliaments. For the assumed ‘hard’ topics (i.e. associated with men) energy and finance, the measured AR and PR revealed a conclusive majority of men in both Slovenia and Spain, but not in the UK. Immigration was initially deemed a ‘soft’ topic, but ultimately established as ambiguous.

The most important finding relates to women MPs’ equality within political debate. The overall finding was that a parliamentary member’s gender could affect their argumentative power. That is, even if women hold the same position, women MPs have fewer opportunities to make their voices heard. Skubic concludes: ‘A significant result was that the presence of women MPs alone does not warrant their participation in debates. Overall, women MPs were found to hold fewer speeches, and are also less often mentioned than men. This was particularly evident in Spain: despite the fact that the percentage of women MPs was relatively high, their power in Spanish parliament was found to be rather low. This is true for both Active and Passive Relevance, which showed us that while women MPs are listened to, they are not heard. They are allowed to speak, but it looks as if it's to no avail.’

During the project, it became clear to the team that understanding the historical and political context of the country in question is essential to analysing power distributions in its parliament. Skubic explains: ‘Named entities were really useful for us, as we could connect the named entity with the person speaking. We think that we didn’t get good enough results for the House of Commons, because we know that Theresa May was listened to quite a lot, and that she spoke quite a lot. But she did not come up in our named entities list because she was not referenced as Theresa May, but as prime minister, which was something we did not consider. This could have been avoided with more background knowledge.’ He adds that, given the right opportunity, and with the benefit of such insights, the team is keen to continue their work on the project.

Future Directions

Skubic notes: ‘The ParlaMint data has so much potential. It's rare that you get so much data gathered in one place. If we hadn’t had the data set, and without the computer scientists, it would have been impossible to do research to such an extent.’ Most recently, additional details have been added to the dataset, such as the political orientation of the party and metadata about ministers (i.e. time span of role etc).

Skubic was only introduced to CLARIN relatively recently, but has since become involved in the ParlaMint project, which encourages researchers in the social sciences to start using corpora in their research. He says: ‘We show them how to use corpora, provide tutorials, so that they can actually use the data that's already there. Based on my own experience (and also as the two literature reviews for sociology and history, written by Skubic and Fišer, 2022, show), sociologists, historians and also political scientists are often not used to using corpora at all. SSH scholars tend to do everything manually, but this past year I have really seen the potential of working with corpora.’

Jure Skubic, Research Assistant, Faculty of Arts, University of Ljubljana and Institute of Contemporary History, Ljubljana

Alexandra Bruncrona, MA Student, University of Helsinki, Finland

Jan Angermeier, Master's student in the Digital Humanities program at Stuttgart University, Germany

Bojan Evkoski, Researcher, Jozef Stefan Institute, Jozef Stefan Postgraduate School Ljubljana, Slovenia

Larissa Leiminger, graduate student, Folkloristics and Applied Heritage Studies, University of Tartu