The Project

At a time when Poland is grappling with a conservative push and growing polarisation among its population, political scientists Agata Włodkowska and Joanna Gajda reconstructed and analysed how the notions of sex and gender featured in two consecutive Polish presidential election campaigns. By analysing the language used by the presidential candidates, as well as the presence of gender-related topics in their election agendas, the researchers show the impact that vocabulary and dominant themes can have during the election process itself, as well as their importance for gender equality more broadly.

The Context

While the presidential election in 2015 coincided with the migrant crisis in Europe, the campaign in 2020 took place during the COVID-19 pandemic and an increasing swing towards illiberalism, visible in the rise of the conservative nationalist party Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (Law and Justice).

The increasingly conservative climate has also meant major setbacks for women’s rights in Poland. The ruling in Poland’s Constitutional Tribunal in favour of a near-total ban on abortion in October 2020 led to a wave of protests and illustrates the deep divides that fracture Polish society. These divides were already visible during the summer presidential elections of 2020, when the conservative Andrej Duda won with a narrow margin.

Methodology

The methodology for this project included quantitative and qualitative content analysis. The researchers compared 23 published, written official election programmes presented by the candidates, as well as seven transcriptions of the debates from the first and second rounds of the elections. The focus of the analyses was on the dominant themes and the vocabulary used.

Outcomes

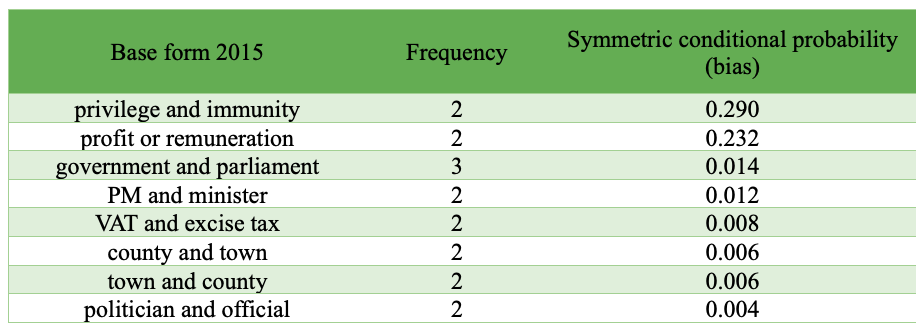

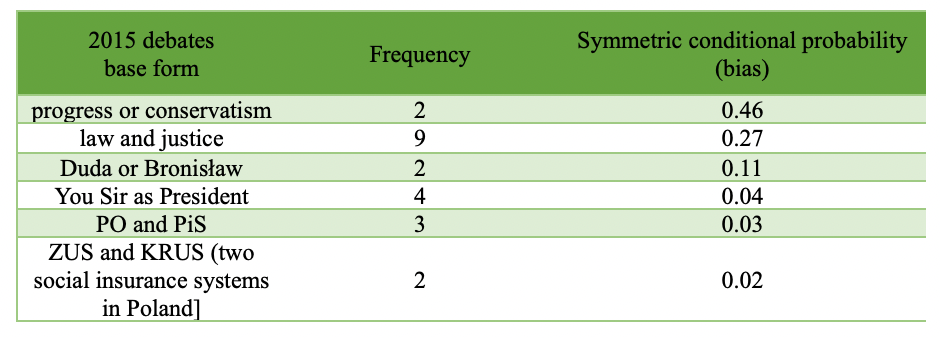

There was a visible difference in terms of language and content during the two campaigns. Based on the analysis of the transcripts, women were rarely recognised by the candidates during the 2015 election campaign. In the few cases that they were referred to, they were usually cast in the stereotypical roles of mothers, carers and nurses. In terms of language, they were barely visible, with little or no use of the feminine form.

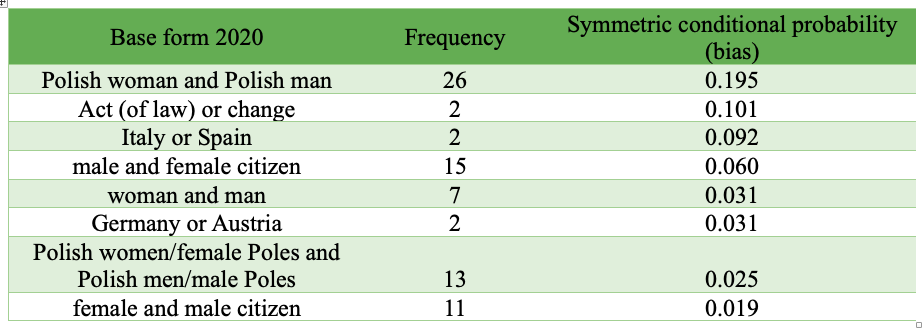

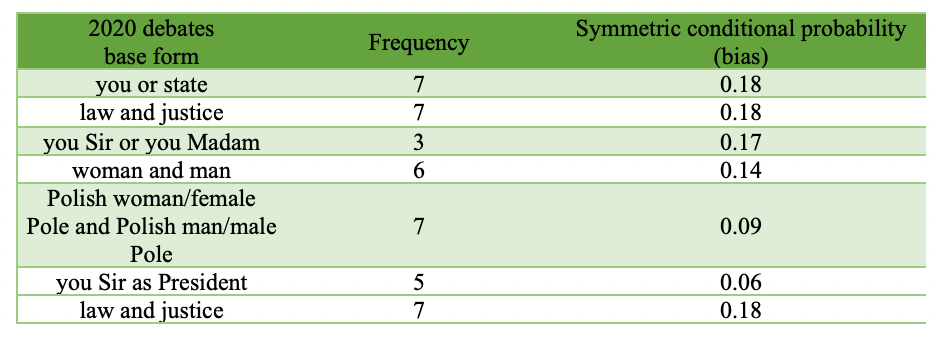

By contrast, the 2020 campaign was characterised by a clear trend towards an increased use of feminine forms, as well as a greater visibility of women. Although still low overall, the greater visibility of Polish women and female citizens as an electorate was evident, for example, from the most common collocations, such as ‘Polish woman and Polish man’ or ‘male and female citizens’. In 2020, women as [feminine form] citizens and the problems they face were referred to more frequently, and specific women known for their functions or achievements were also recognised. Overall, Polish women were increasingly perceived as socially and professionally active individuals, for instance as (female) experts, directors, MPs, senators or clerks. However, the word ‘women’ is still most often used in contexts relating to maternity, health and domestic violence in both the election programmes and televised debates.

What came as a surprise to the researchers was the significant difference between the two formats. Whereas some positive trends were detected in the online election statements, as described above, the language and content in the spoken debates did not show these changes. Overall, the feminine forms were used much less often in debates, and women’s visibility was also considerably lower than in the election programmes.

Włodkowska notes: ‘There was one candidate […] who was very focused on feminine endings in the programme. […] But during the debates, there was almost nothing […]. And the same was the case with stereotypes. So it seems that using those masculine and feminine forms, and presenting the open mind and programme, was only some kind of tool to get the support of women.’

In terms of content, some dominant themes prevailed during both campaigns. Overall, the portrayal of women was largely based on a stereotypical image: women’s visibility was often limited to topics such as reproductive rights, social and economic rights, violence against women, and women’s participation in politics. Candidates referred to women almost exclusively in terms of family, or their role as a mother or care-giver. In this way, motherhood is permanently inscribed into the image of Polish women, which can have broader social consequences.

Another theme that was present during both election campaigns was the portrayal of women as needing protection and help from men, while women’s agency was less frequently recognised. Gaida notes: ‘It frames women as a less powerful, weaker part of society. And it also elevates the men. It’s like a parent-child relationship, where you cannot be free, you cannot make your choice, you need to be told what to do, or what is good for you. It's quite clever, because it comes across as positive […] but it actually frames women as unable to look after themselves or take responsibility.’

In conclusion, despite the fact that the use of language appears to have evolved by the 2020 campaign, the dominant narrative surrounding women remains unchanged. Statements tended to reinforce the stereotypical gender divisions, as well as uphold the myth of ‘protection’. Problematically, the authors point out that this myth may perpetuate the elements of structural violence, that is, keeping women away from the public and state spheres by keeping them in the private sphere, and controlling them and marginalising them by convincing them that they are weak and need to be protected. Changes in context, such as the women’s protests, also seem to have had no noticeable effects on the rhetoric.

However, while the change in language may be only superficial in politics, the researchers sense that, more widely, the use of and discussion about grammatically feminine forms signals real engagement with the issue. Gajda says: ‘In the programme of politicians, they use [grammatically feminine forms] only as a tool. But in society, we try to use it and I feel that something is changing, because people are thinking about it. But in the election programmes, we felt that it was only for finding another way to get votes; there is no real impact.’

Gajda notes that it would not have been possible to conduct this kind of research without CLARIN’s tools. She says: ‘CLARIN is especially useful for creating and organising large datasets, and being able to work with them online in research teams.’ She adds that for this project, it was important that it was possible to continue their research by creating a dataset for future campaigns, such as in 2025, and compare and observe changes.

She is keen to show how these tools can be useful to political scientists, who do not yet routinely use them in their research: ‘The ability to look for differences between the texts of programs and debates and natural language is very interesting. The [Korpusomat] tool is trustworthy and methodologically responsible. It allows linguistic analysis without being a specialist. It draws attention to the specifics of the texts and allows users to deepen the context for the more characteristic phrases later on in a qualitative analysis. It would be impossible to get these results any other way. Political scientists have a wide range of possibilities to use the tool, because they work with a large amount of written data.’

Joanna Gajda, PhD, independent researcher